Basel: Faulty – The Financial Crisis Revisited

In Which it is Proven that Bad Regulation Caused the 2008 Financial Crisis

The 2007 - 2008 Financial Crisis was caused by excessive systemic leverage.

But what caused leverage to spike after 2000?

Answer: the Basel capital standards authorized extreme leverage for European banks, supercharging credit risk and illiquidity. US shadow banks happily followed suit.

US commercial banks held in as solid as a rock because they were held to a stricter standard,

Scapegoating banks, policymakers responded with unnecessarily onerous regulations.

Charles Cranmer charlescranmer@gmail.com

Abstract: In this paper I will take a revisionist look at the causes and consequences of the 2007-2008 Financial Crisis. I will argue that its most commonly-cited causes – deregulation, financial innovation, savings gluts, and fraud – were inconsequential. I will contend that the Crisis had a single overriding proximate cause – a spike in the leverage of European Banks and US “Shadow Banks” between 2000 and 2008. This leverage spawned a corollary jump in systemic illiquidity and a degradation in credit standards. The critical question is: What caused systemic leverage to soar? The answer is bad regulation. Specifically, the Basel Capital Standards.

Because policymakers then and since have failed to grasp Basel’s central role in causing the Crisis, they have responded to it with a misguided regulatory regime intent on punishing “the banks”. Today, this regime (e.g., Dodd Frank, Basel III, arbitrary and draconian “stress tests”) amounts to the de facto nationalization of our commercial banking industry. It has severely damaged the industry and hindered economic growth. We must take immediate action to overhaul today’s onerous burden of bank regulation.

THE CRISIS

“The best laid schemes o’ Mice an’ Men

Gang aft agley

An’ lea’e us naught but grief an’ pain

For promis’d joy!” . . . . . Robert Burns

More than a decade has elapsed since the Financial Crisis of 2007-2008. It is high time that we all step back and take a clear-eyed look at its actual causes and consequences.

Since the crisis, bank regulation in the United States has gone grievously off the rails. The perfect storm of Basel III, Dodd-Frank, and subsequent regulatory accretions amount to the back door nationalization of our commercial banking industry. Today, few major management decisions are not subject to regulatory say-so.

Why are our legislators and regulators intent on imposing such an oppressive regulatory regime? Simple: they have failed to grasp the true nature of the Financial Crisis. Misunderstanding the crisis, policymakers have drawn all the wrong lessons from it. They fervently, and mistakenly, believe that the crisis was a failure of free markets that called for heightened government control of the banking system. Many are still wedded to the myth that the crisis stemmed from the mass criminality of Wall Street fat cats.

This is malarkey. The central underlying cause of the crisis was neither de-regulation nor too little regulation but bad regulation. Specifically, the Basel Capital Standards. Basel installed a regulatory regime suffused with perverse management incentives. Most perniciously, it mandated egregious leverage for European banks. US “Shadow Banks” happily followed suit. This leverage sent the Western financial system into a mad scramble for the marginal asset and necessitated a wide-open fire hose of short-term funding.

Let’s get one thing straight from the get-go: the financial crisis was not caused by “the banks.” (By “banks” I mean US “commercial banks”; deposit-taking institutions regulated by the Federal Reserve, FDIC, and/or the OCC.) Lehman Brothers was NOT a bank; it was an SEC-regulated broker dealer. Washington Mutual was NOT a bank; it was an FSLIC-regulated thrift. AIG was NOT a bank but an insurance company with a thrift subsidiary. UBS was a Swiss bank with US brokerage operations regulated by Swiss authorities and the SEC. General Motors was a finance company with a car maker attached. GE was, well, whatever GE was.

Yes, a few US banks (e.g., BankAmerica and Citigroup, the perennial weak link) got caught up in the sub-prime frenzy. But by and large, US commercial banks were not perpetrators of the crisis but victims of the perverse Basel regime that governed global financial institutions.

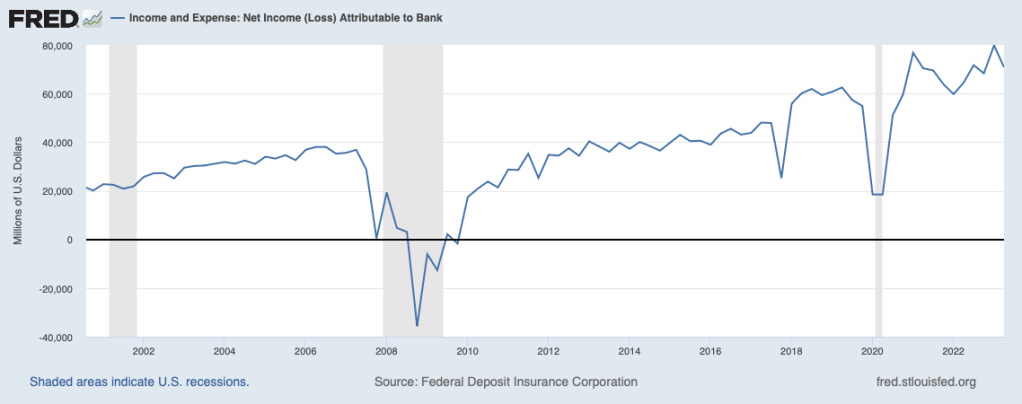

In fact, US banks weathered the financial crisis with stalwart resilience. The worst year for FDIC-insured commercial banks was 2008, when the industry lost an aggregate $12 billion after earning $128 billion in 2006. In other words, the industry in 2008 gave back 10% of what it had earned two years earlier. That does not sound like financial collapse to me. In fact, $12 billion was one fourth of what our government spent to bail out GM.

All of this demonstrates that the pre-crisis regulatory regime – flawed and redundant though it may have been — proved more than sufficient to keep the banking industry – and our economy – afloat as the Basel-driven hurricane did its worst. There was no need for further, more onerous regulation. No need for Dodd-Frank, no need for Basel III, no need for stress tests, no need for living wills or any of the other busy work that Washington delights in imposing on the industry. But policymakers had to blame somebody, and commercial banks were very convenient scapegoats.

THE ONLY BAILOUT WAS OF EUROPE (oh, and GM)

To buy US mortgages, European banks needed dollars. This meant that to fund their purchases they needed either to borrow dollars or swap into dollars from the Euro or Sterling. At first this was no problem: many European banks owned US subsidiaries (First Boston, Bankers Trust, Paine Webber.) Money Market Mutual Funds (MMMF) were eager buyers of the short-term paper.

But when Lehman Brothers failed and a major MMMF “broke the buck”, there was a run on all MMMF’s. They would no longer fund foreign banks.

This was a problem for US shadow banks, most of which scurried under the Fed umbrella to access its lending programs. But It was a far worse problem for European banks who faced a double whammy. Because the Fed’s capacity to lend to foreign banks was limited, they had no way to obtain DOLLAR funding. This left them open to an immense exchange rate mismatch. Hyun-Song Shin’s “ The Global Banking Glut ” discusses this issue in depth.

To close this currency mismatch, the Fed lent hundreds of billions of dollars to foreign central banks who then divvied out the dollars to their neediest constituents. In his magisterial book “Crashed”, Adam Tooze chronicles these efforts.

In a nutshell, then, the crux of the Crisis was a Fed bailout of Europe.

Recent events surrounding Silicon Valley Bank and other regional banks underscore the folly of our current regulatory structure and the shocking ineptitude of regulatory authorities. It is now abundantly clear that the regulations disgorged by policymakers over the past 15 years have severely damaged our banking system. Policymakers will never get regulation right until they accept that their view of the 2007-2008 Financial Crisis is dead wrong.

Just to be clear: no one – least of all me – believes that banks should be entirely unregulated. My belief, and I think, the belief of most Americans, is that regulation is sometimes necessary, but that less regulation is almost always preferable to more. That’s not because we have blind faith in the free market. It’s just that we have a lot more faith in the free market than we have in the D.C. bureaucracy.

In this article, I will present what I am convinced is the truth about the Financial Crisis. I am hopeful that if we all allow ourselves to examine the crisis dispassionately, we will be persuaded to reconsider the unnecessary regulatory constraints that now hobble the banking industry and our economy.

Note: Henceforth, I will refer to the 2008 Financial Crisis as the Basel Financial Crisis (BFC)

Throughout this paper, I will use the term “Bank” to refer strictly to US commercial banks. Thus, “Banks” are deposit-taking institutions regulated by the FDIC, the OCC, and/or the Federal Reserve.

Those firms that were most deeply involved in the sub-prime business I will refer to as “Financials”. These include European banks, brokers and other shadow banks like AIG, and a few US commercial banks. Also, when I say “policymakers” I mean our politicians, our regulators, and their academic enablers. One might reasonably include the media in this cohort. When startled, they, too, all stampede in the same direction.

BASEL IN A NUTSHELL

First, here is some background on Basel I:

Historically, bank regulators have required banks to maintain a minimum capital base. This capital cushion protects bank creditors (mainly depositors) against losses in the bank’s asset portfolio. In practice, modern bank capital requirements have ranged between $5 and $10 in capital for every $100 in assets. This equates to a 5% to 10% leverage ratio.

Very simplistically, a 5% leverage ratio means that a bank with assets of $100 can sustain a $5 loss before shareholders are wiped out. Any greater loss is absorbed by creditors. It’s roughly analogous to buying a $100,000 house with a $95,000 mortgage and a $5,000 down payment. (Your leverage ratio is 5%.) If the value of your house drops, the most you can lose is $5,000. Anything more than that and the bank takes the hit.

Prior to Basel, capital requirements were determined by individual national regulators. European banks and US banks had roughly similar capital ratios, although there were big differences in how those ratios were calculated. For example, German banks had large “hidden reserves” of investments in industrial companies whose shares had market values worth far more than their book values.

Japanese banks were the big outliers. At the time Basel was ratified, Japan was in the midst of colossal stock market and real estate bubbles. On a GAAP basis, Japanese banks had minimal capital (i.e. stratospheric leverage) but like the Germans, they had immense unrealized gains on investment holdings and real estate. Of course, in 1990 the bubble burst with catastrophic consequences for the country. Over the next few years, all of Japan’s major banks either failed or needed bailouts.

In 1988, Basel inaugurated a sea-change in bank regulation intended to standardize international rules. This change made sense in theory as regulations occasionally do. Its objective was to make a given bank’s capital requirement correspond to the riskiness of that bank’s balance sheet. Its method was to assign “risk weightings” to each class of assets.

Sovereign debt (e.g., Treasury Debt) was assigned a risk weighting of zero – no capital required. Mortgages were assigned a risk weighting of 50%, requiring half the capital backing of a commercial loan (100%.) Thus, a bank whose asset base consisted of 100% Treasury Bills would require almost no capital, while a bank specializing in commercial lending would require the maximum.

But lurking within Basel was a latent unintended consequence; it would sharply amplify systemic leverage. This leverage would make financial firms much more vulnerable to a large loss, much as a top-heavy ship is vulnerable to a rogue wave. By 2007, some European banks were off the charts. The leverage ratio for Barclay’s was 2.1% and 1.4% for UBS. Even mighty Deutsche Bank, that paragon of financial probity, was leveraged nearly 100 to 1.

European bank balance sheets began to balloon around 2000. As is further discussed below, the cause was the advent of the Euro. Suddenly, banks in the larger European countries could make large loans to “periphery” nations (the Baltics, Greece, Portugal) without worrying about foreign exchange risks. Because Basel rated these loans “zero risk”, there was no regulatory constraint on the volume of loans they could make. A couple of years later, they discovered that the same was true of AAA rated sub prime PMBS, and the rest is history.

I estimate that between 2000 and 2007 European banks booked nearly €7 trillion in “excess” assets due purely to increasing leverage. This meant that, by 2007, the European banking system held roughly €12 trillion in assets beyond what would have been acceptable leverage of 5%. This was fully a third of European banking system assets. Many, if not most, of these assets were US domiciled.

Permit me to observe that these were very, very, very big numbers. Seven trillion Euros was more than three times China’s dollar reserves. It was roughly equal to the total value of US commercial bank loans. It was roughly equal to the US national debt at the time.

European banks had little choice but to take on as much leverage as Basel allowed. It would have taken much fortitude (and a wise and supportive board of directors) for a management team to resist. A bank that took advantage of maximum leverage under Basel (say 2%) would have had more than twice the return on equity of a bank that employed more conservative (but still aggressive) leverage of, say, 5%. Not only would this have left management open to criticism from shareholders and governments (European nations have a strange fetish for “National Champions”) but the bank would have become vulnerable to an acquisition.

BARCLAYS’ ASSET GLUT

Nothing underscores the pernicious impact of Basel more clearly than the following graph. I have borrowed it from “ The Global Banking Glut ”, a 2012 paper by economist Hyun-Song Shin that is far the single most important analysis of the crisis. While Shin never explicitly blamed Basel for the crisis, his analysis clearly pointed that way.

This graph shows that from 2002 to 2007, Barclays’ total assets tripled by £800 billion from £400 billion to £1.2 trillion as measured by UK GAAP (generally accepted accounting principles.) This is a 5-year compound annual growth rate of a whopping 25%. But by Basel’s “risk-weighted” standards, Barclay’s assets “only” doubled to £400 billion. “Steady as she goes,” by Basel standards.

To illustrate the effect of Basel on bank balance sheets, let’s consider 2 different highly simplified scenarios:

Let’s say that in 2000, Barclay’s starts out with $1,000 in loans and $50 in equity. It is fully compliant with 5% regulatory capital standards

Scenario 1. Over the next year, Barclay’s books $200 in commercial loans and retains $10 in equity. Thus, it ends the year with $1,200 in assets and $60 in equity. In this case, the bank will be in compliance with both Basel standards and GAAP standards. This is because Basel assigned commercial loans a 100% risk weight.

Scenario 2. Over the next year, Barclays makes $1,000 in loans to Greece and retains $10 in equity. Thus, at year end, Barclay’s will have $2,000 in assets and $60 in equity.

From a GAAP standpoint, Barclay’s will be undercapitalized by $40 ((2,000*.05)-60) and will need to issue new equity and suffer the resulting dilution. Implicitly, sovereign risk is weighted 100% under GAAP, the same as any other asset. In contrast to the case under GAAP, Barclay’s under Basel will be in a position to accelerate its leverage next year.

Now consider the difference under Basel. Under Basel, Barclay’s will be overcapitalized by $10 million. This is because sovereign credit had a risk rating of zero; Barclays could add as much sovereign credit as it wanted with no capital burden. The same thing was true of AAA rated subprime assets. These carried a risk weighting higher than zero, but the impact on Barclay’s balance sheet was essentially the same.

To put it another way, as far as Basel was concerned, Barclays in 2007 held £800 billion in assets that simply didn’t count. But even though Basel didn’t count them, they still carried risk and needed to be funded. As I emphasize throughout the paper, Basel’s critical flaw was that it greatly amplified liquidity risk. These additional assets were not funded with deposits, but with short term wholesale borrowings.

Not to put too fine a point on it, but it’s a mystery to me how any reasonably informed individual could have looked at Shin’s graph and not drawn the same forehead-smacking conclusion that I did: “Aha, now I get it: Basel caused this whole mess.”

WE MUST CHANGE THE REGULATORY DEBATE

Let’s say that you ask a bank regulator what her mandate is. If she is honest, she will say, “my mandate is to remove every vestige of risk from every bank to eliminate any possibility of even a single big bank failure.” (This was largely written before the Silicon Valley travesty.) A corollary objective is to ensure that “neither I nor any of my superiors is ever publicly eviscerated in front of a congressional banking committee.”

It is imperative that we rewrite this regulatory mandate. By attempting to eliminate all risk from the banking system, regulators impose a heavy burden on the economy. Credit cannot be effectively allocated if banks are precluded from taking prudent risk. The alternative is for our government to become more directly involved in credit allocation. I think everyone will agree that it is preferable for private institutions to assume risk based on economic incentives and using their own capital than for the government to distribute credit based on purely political agendas.

A more constructive regulatory objective would be something like “what is the least amount of bank regulation that is consistent with economic growth at reasonable risk.” This is another way of saying that a regulator’s top priority should be to establish the incentives that attract the best managers into the industry and pursue the best practices once they get there. (See my blogpost “Law and Order: FDIC” .) To achieve this end, it is essential that we all draw the correct lessons from the BFC.

But there’s a problem: The same brains that brought us Basel I, Basel II, and the Basel Financial Crisis are still in charge. Evidently ignorant of (or, perhaps, in denial of) their central role in causing the BFC, regulators have shed none of the hubris that spawned the original Basel standards in 1988. Given their track record, I think we should be skeptical of their current and future efforts.

In 2012, regulators rolled out Basel III, which was an abrupt about face in regulatory policy. Whipsawing from Basel II’s abandonment of regulatory supervision, Basel III, along with Dodd-Frank, imposed an oppressive regime of punitive restrictions, obscure directives, and regulatory micro-management. Plenty of policymakers regard this regime as a rousing success because there have been no large bank failures since the BFC (at least, not until SIVB.) But this has come at an immense cost to our economy. To cite just one example; the regulatory kibosh on construction lending, along with the post-crisis destruction of the mortgage industry largely explain our current severe housing shortage.

Many policymakers do not understand or trust free markets. Some are deeply resentful of those who succeed in the private sector. Many politicians – Republicans and Democrats alike – will seize on any opportunity to assert control over free markets. They seem convinced that they alone possess the knowledge and wisdom to manage an unimaginably complex economy. It evidently has never occurred to them that the economy might be better “managed” by hundreds of millions of private citizens freely making billions of independent decisions every day to satisfy their own wants and needs.

To the extent that the American public thinks at all about the BFC, their attitude tends to be uninformed and conspiratorial. Most are more interested in rooting out scapegoats than in teasing out the truth. They say things like “American working folks were duped out of their homes by Wall Street fat cats who were all bailed out by special interests, leaving Main Street broke.” Some progressive politicos have made such statements explicitly.

Nor have consensus economists been of much help in getting to grips with the BFC. They tend to regard the BFC as just another of those “exogenous shocks” that hits every now and then, messing with their models. They tend to focus myopically on its “proximate” causes, neglecting to dig for more fundamental prior, or “ultimate” causes – Basel, for instance.

Two recent retrospectives of the BFC present different versions of the consensus narrative. In “ What Happened ,“ Mark Gertler and Simon Gilchrist offer up a “mea culpa” that helps explain the failure of economists to anticipate the BFC or to understand it afterward. Essentially, their pre-BFC models deemed such events impossible. They admit, “At the onset of the crisis, the workhorse macroeconomic models assumed frictionless financial markets.” Earth to economists; in what world have financial markets ever been “frictionless?” Anyone who has ever filled out a mortgage application knows that friction is constantly grinding away at financial efficiency. The authors might just as well have said: “At the onset of the crisis, economists had no clue how a modern economy actually worked.” They largely attribute the crisis to an apparently exogenous housing bubble.

To digress just a bit, it was the tendency of consensus economists to ignore the financial system that so riled up the great curmudgeon Hyman Minsky. He believed (far too strongly, in my opinion) that the financial system was the principal source of instability in a capitalist economy and ought to be tightly controlled by the government, if not nationalized. Like many economists of his day who came of age during WWII (e.g., Galbraith, Samuelson, Heller, Tobin), he was overconfident in government’s ability to manage things competently.

In “ Ten Years Later “, Joseph Stiglitz, too, emphasizes that deep flaws in their models blinded economists to the approaching crisis (except himself, of course.) So far, so good. But he then goes on to blame the BFC on the usual bogey men; insufficient regulation, financial innovation, and “a culture of bad financial behavior.” Like most commenters, he conflates Banks with Financials: “Anybody looking closely at banks’ balance sheets should have been horrified by what was going on. Americans weren’t just borrowing; the mortgages that they were borrowing were exceptionally dangerous.” As we mentioned above, the truth is that very few Banks had any direct exposure to the sub-prime business.

Neither article discusses any role for European banks or Basel. Both articles identify leverage as a key causal factor of the BFC, but neither bothers to explore what might have driven the spike in systemic leverage after 2000.

In his recent book, even Ben Bernanke echoed the consensus view:

“Most research on the bubble has focused on three factors; mass psychology, financial innovation that reduced the incentives for careful lending, and inadequate regulation.”

I have immense respect for Ben Bernanke, but this analysis of the BFC simply is not helpful.

I have only recently come across a paper that does identify Basel as a key factor in the crisis, if indirectly. In “The 2008 GFC: Savings or Banking Glut” (2019), Robert N. McCauley endorses Shin’s view of the BFC. Then he goes one step further, saying “ . . . Basel II . . . permitted US securities firms and European banks to pile 50 or more dollars or Euros on top of every dollar or Euro of equity.” This paper vividly describes the strategic desperation of European banks to generate US assets, apparently without any consideration of the risks.

CAUSAL INFERENCE AND HOW TO READ THE CHART

To develop a convincing argument for my thesis, I will adapt to the best of my ability an analytical technique known as “Causal Inference” (CI.) This methodology is most closely associated with Judea Pearl, a computer scientist and statistician who teaches at UCLA. The basics of CI are detailed for neophytes (like me) in his terrific book “The Book of Why.”

For Professor Pearl, the main application of CI is artificial intelligence. With it, he attempts to bridge the gap between traditional statistics, which studiously – almost pathologically — abjures drawing conclusions about causation, and the practical need to infer causes from empirical evidence.

My objective is to use CI to prove that the Basel Capital Standards caused the BFC. By “prove” I mean that after enumerating all the BFC’s “proximate” causes, I hope to show that Basel was the driving force behind the most important of them. Therefore, if one agrees with my list of proximate causal factors, and if one accepts that Basel’s influence on each is in line with my estimates, then one must agree that “But For” Basel, the GFC would not have occurred. Or, at least, it would have looked much different. I can think of no other “But For” candidate that is nearly as convincing.

Now for the chart itself. The first column includes only one item: Basel I. In this simplified chart, I consider Basel I to be the single most salient underlying cause of the BFC.

The arrows emanating from “Basel I” point to an array of “proximate causal factors.” These are essentially all the near-term factors that might have had a role in precipitating the crisis. It’s a bit like a reverse decision tree.

As you can see, Basel’s influence on each factor ranges from dominant to none. A dominant influence for “leverage” and “illiquidity” means that Basel was almost exclusively responsible for the financial system’s most extreme pre-crisis imbalances. These factors, in turn, were dominant causes of the BFC.

On the other hand, Basel had no influence on Europe’s adoption of the Euro, which was a moderate contributor to the crisis. Most factors for which I could perceive no causal influence I categorized as “minimal”, not “none.” I have learned that the influence of prior events on subsequent events can be complex and subtle.

Again, mine is a rudimentary application of CI. In a more sophisticated approach, each “causal factor” would have innumerable causes, cross-correlations, reflexivity loops, and confounders. But to avoid a spiderweb of lines and arrows heading in every direction, I have isolated the impact of Basel alone. Rather than draw a causal diagram for each factor, I will use text to examine each in detail.

GREED AND FRAUD: A COUNTERFACTUAL

The second causal inference chart attempts to tease out the role of “greed and fraud” in causing the crisis. Many Americans (and not just the layman) are deeply invested in the myth that fraud lay at the heart of the BFC.

This chart is a “counterfactual” in the sense that greed and fraud did not play a central role in causing the BFC There was certainly fraudulent behavior in the BFC (as there is in many human endeavors, especially those that involve money) but the crisis would have occurred even if there had been no fraud at all.

If one wishes to argue convincingly that fraud was the predominant cause of the crisis, one must account for several anomalies which are all readily explained by Basel:

First, one must explain why Financial managers suddenly turned pathologically greedy in 2000 (perhaps greed is a zero-sum game and in 2000 it shifted from internet speculators to bankers.) Were Financial managers really such saints prior to 2000? The truth is that what really changed were the regulatory incentives that altered competitive behavior.

Plus, one must explain why this moral slump was so selective. Why did G20 economies like Japan, Australia, and Norway not succumb? What moral attributes did these societies possess that endured post-2000? Why were Canadian banks exempt, except those with US operations?

Plus, one must explain why US commercial bankers maintained their moral equilibrium while European banks and US shadow banks went nuts. Were these bankers morally superior to everyone else? Or, as is my contention, did regulators hold them to a higher financial standard than that imposed by Basel.

Finally, one must explain why “No Wall Street CEOs ever went to Jail” for their role in the crisis. The implication is that their wealth and privilege made these CEO’s immune from prosecution. But this is ridiculous; prosecutors were positively drooling to perp walk CEOs out of their offices. They didn’t go to jail because, however reprehensible their behavior may have been, they did not commit crimes.

Along with fraud, many identify “moral hazard” as having played a central role in the crisis. “Moral hazard” is also known as the “too big to fail” problem, or “heads I win, tails you lose.” The idea is that pre-crisis financial managers took excessive risk (mainly, too much leverage) because they knew that if they succeeded, they would make fortunes, but if they failed, they would be bailed out by taxpayers. Moral hazard presupposes that managers have no “skin in the game.”

But moral hazard played only a limited role in the GFC for the following reasons:

In fact, many senior managers did have significant skin in the game. Most managers of US Financials held large positions in their own firm’s shares. However, this was not generally true of the European banks.

In any “bailout,” equity holders typically are wiped out. In the case of banks, only depositors typically are made whole. Thus, equity holders will not “win” if the bank fails. There was no reason for shareholding managers to take excessive risk because they were aware that they’d lose everything if they failed.

Nearly all the big US firms that failed or came close to failing in the BFC were not banks but shadow banks. Except for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (two critical players) there was no regulatory commitment, either explicit or implicit, to support Shadow Banks in the event of failure. The willingness of creditors to continue to lend to over-leveraged Financials stemmed not from an implicit government guarantee, but from a misplaced confidence in the collateral. However, I concede that the bailout of Bear Stearns allowed Lehman to borrow and stay in business longer than it otherwise might have.

Having said this, I should point out two important groups of players who emphatically did not have skin in the game. First, there was an army of “Wall Street” traders who couldn’t have cared less about the welfare of the firm they worked for. Their sole incentive was to generate trading profits that were as large as possible with positions that were as large, and as risky, as necessary. Once year-end had passed and they had received their bonuses, they were indifferent about the fate of their positions, or the firm.

Similarly, mortgage originators at the independent subprime mortgage companies did not care about the riskiness of the loans they generated. Their commissions far exceeded any investment they may have had in the company.

To be sure, moral hazard is a real problem. It was the primary driver of the late 80’s thrift crisis. It just didn’t play much of a role in the BFC. We are always fighting the last war.

For those who insist on finding fraud and corruption at the heart of the BFC after everything I’ve said, I suggest turning your gaze across the pond. In Europe, one sees such brazen malfeasance by bankers in Ireland, Spain, Greece, the UK, and, especially, Iceland that it makes Dick Fuld and Angelo Mozilo look like choirboys (see Faisal Islam’s superb book “The Default Line.)

DID BASEL MAKE THE CRISIS INEVITABLE?

In my opinion, from its inception in 1988, Basel was a crisis in search of an asset. It found two.

First, it found Euro-denominated assets. With the inauguration of the Euro in 1999, big European banks suddenly found they could make huge loans to other Euro members like Greece, Spain, Portugal, and the Baltics without worrying how those countries would obtain the currency to pay them back. Better yet, Basel rules required no capital for sovereign loans, so their return on equity was effectively infinite. In the early 2000’s, the rush to lend was so powerful that loans to Greece and other “periphery” European nations carried interest rates only slightly higher than, and sometimes in line with, loans to Germany.

Two superb books that examine the central role of European banks in the crisis, each from a different angle, are “Crashed” by Adam Tooze and “The Default Line” by Faisal Islam. Tooze takes a macro approach, thoroughly examining policy decisions and financial flows leading up to, and during the crisis. Islam’s book is a highly entertaining romp through the crisis, zooming in on critical personalities and issues, most European, that have been largely ignored by most observers.

Next, European banks discovered American subprime mortgages. As interest rates dropped to zero post-2000, US home prices soared, attracting a swarm of subprime mortgage companies to scavenge this burgeoning home equity. Many of these subprime loans were refinancings of existing conventional mortgages. Lenders charged deceptively low “teaser” rates with exorbitant fees to these poorly qualified buyers.

Crucially, these sub-prime loans were categorized as mortgages by Basel and therefore “low risk”. This meant that they required much less capital than did a standard loan. Once securitized into Private Mortgage-Backed Securities (PMBS), the AAA tranches that banks retained required even less capital. Some legitimately could be levered more than 100 to 1.

Thus was born a perfect storm of brokers who could originate a virtually limitless volume of mortgages, and a financial industry with no regulatory constraint on the volume of sub-prime mortgages they could buy, package into securities, and sell, while retaining the “AAA” slices for their own books.

Because Basel blessed this egregious systemic leverage and illiquidity, I consider it a “necessary” cause of the crisis. Something enabled European banks to become so highly leveraged, and I can think of no explanation other than Basel. Without this untoward leverage, subprime lending could not have done the damage it did. Subprime loans and Basel together comprised both necessary and sufficient causes of the BFC. A crisis was all but inevitable.

Think of it this way; Suppose a regulatory package like Basel 1 were enacted today. Then ask yourself:

What is the probability of a future financial crisis given a regulatory regime that permits 50-to-1 leverage (versus ten-to-one ish today), 80% short term funding, unlimited currency mismatches and allows managements to value their own bank’s assets? Oh, yes, and deems subprime mortgages “low risk.”

PROXIMATE CAUSES OF THE 2007-2008 GREAT FINANCIAL CRISIS

Below I examine in more detail the influence of Basel and other factors on each of the “Proximate Causes” that spawned the crisis.

Leverage of Financial Institutions

Excessive systemic financial leverage was the overriding proximate cause of the BFC. Blessed, if not encouraged by Basel, this leverage nearly brought down the Western financial system. Many, if not most of the ancillary causal factors– systemic illiquidity, credit deterioration, the sub-prime lending bubble, Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDO’s). and credit default swaps (CDSs) — derived from this egregious systemic leverage.

Another factor that contributed to systemic leverage was 2004 relaxation of the net capital rule for US broker dealers (Lehman, Goldman, Merrill Lynch, plus US subsidiaries of Eurobanks) This was largely a response to the Basel-driven leverage of Eurobanks and allowed broker / dealers to assume additional leverage. Some brokers increased leverage to as high as 30 to 1. This ruling enabled higher systemic leverage, but not as much as one might expect. That’s because this rule applied only to broker-dealer subsidiaries; their parent companies had already become highly leveraged.

It is significant that, despite the doubling in European bank leverage and the attendant rise in illiquidity from 2002 to 2007, credit ratings from Moody’s and S&P remained mostly stable. Clearly, the rating agencies fully bought in to the Basel fantasy, suspending any capacity for critical thought. One can only wonder whether either rating agencies or regulatory agencies had even the most rudimentary understanding of the businesses they are tasked with overseeing. Then or now.

At the risk of redundancy, permit me to reemphasize the one key lesson of the GFC that NO ONE seems to get: the pre-crisis US commercial bank regulatory regime worked far better than could have been expected and saved the US, and perhaps the world economy. The stalwart resilience of commercial banks was largely thanks to the FDIC (kudos to Sheila Bair) and the OCC, which wisely spurned Basel and required US banks to maintain leverage ratios above 5%.

The best action we could take today is to scrap Basel and Dodd Frank, de-nationalize the commercial banking industry, return the pre-crisis regulatory framework, and then build on that.

Illiquidity of European Banks and US Shadow Banks

The BFC was a classic liquidity crisis, emphatically not a solvency crisis. That is, the BFC was a run, a panic – a sudden loss of confidence in the ability of counterparties to make payment or obtain good collateral. (See the appendix “A Primer on Solvency and Liquidity” at the end of this essay.) The solvency of most US institutions was never threatened. In his superb book “Lehman Brothers and the Federal Reserve” Lawrence Ball argues persuasively that Lehman may not have been insolvent when it declared bankruptcy, and almost certainly had sufficient collateral to borrow.

The Basel leverage game had a fatal flaw; to goose leverage, Financials needed funding – lots of it. Heightened leverage does not necessarily spawn illiquidity: a highly leveraged firm can elect to fund itself with longer term debt. But pre-BFC, the very low yields of AAA PMBS assets compelled Financials to fund these securities with short term, often overnight borrowing to get a positive spread. Thus, Basel rules had the effect of transmuting credit risk into liquidity risk. A 2001 change to the obscure “recourse rule” reduced exposure to the riskiest PMBS tranches and greatly increased exposure to the AAA tranches. This reduced credit risk and greatly amplified liquidity risk.

How can we be certain that the BFC was a liquidity crisis and not a solvency crisis? Because the AAA rated PMBS tranches that caused most of the losses and were written down as much as 50% in the heat of the panic, soon rebounded to 100 cents on the dollar, or nearly so.

Even the FCIC (Financial Crisis Investigation Committee) with every reason to dissemble, said, “most of the triple A tranches have avoided actual cash losses through 2012 and may avoid significant unrealized losses going forward.”.

Most Financial borrowings were collateralized. From the creditor’s standpoint, this made them seem all but risk free since the collateral was AAA rated and borrowings were often over collateralized. Pre-crisis, these secured borrowings were mostly Repo and Asset-Backed Commercial Paper (ABCP.) ABCP mostly financed off-balance sheet entities called “SIV’s” which housed the AAA slices of PMBS. Bear in mind that regulators were aware of, and validated, all of this.

The protection provided by collateral proved illusory when the crisis hit. As liquidity vanished, Financials were unable to obtain good collateral. They were compelled to sell their AAA PMBS at fire sale prices. This drove a downward spiral in the prices of all assets.

Commodities and Foreign Exchange – The Real “Bubbles” of the 2000’s

The behavior of foreign exchange rates leading up to the crisis was extreme. From 2000 to 2008 the value of the Euro doubled versus the dollar. There were many possible reasons for this. For one thing, the launch of the Euro in 1999 necessitated large portfolio shifts worldwide. Arguably the Euro had been sharply undervalued from the get-go. Also, the US ran large trade deficits with the Euro area throughout the 2000’s and US interest rates were consistently lower than Euro rates. But none of these factors seem adequate to explain a near doubling in the Euro’s value. Clearly, there was something else going on.

I should mention that over this same period, the UK Pound Sterling appreciated 30% against the dollar – not nearly as much as the Euro.

There are a couple of ways in which Basel leveraging might have amplified the Euro’s strength. Possibly, by lending in US dollars, the consolidated leverage of Euro financial institutions would have been consistently understated as the dollar’s value declined. This would have given them even greater capacity to lend. Finally, remember that Euro banks were funding US asset growth with US funding. Initially, they did not need to buy dollars, so their operations did not put demand pressure on the dollar. It is surely significant that the Euro peaked in July 2008 and then collapsed as the BFC gained steam, despite immense support from the Federal Reserve.

Related to the dollar’s weakness was a shocking spike in commodity prices between 2003 and 2008. This, not American real estate, was the true “bubble” of the 2000’s and is an imbalance that is often overlooked in analyses of the crisis. In these five years, oil prices, gold prices, and copper prices all at least quadrupled in dollar terms. Yet conventional inflation measures in G-8 countries remained restrained – hence “the great moderation.”

It was the astonishing economic expansion of Red China, along with construction booms in the US and Europe, that drove commodity prices higher. Low Chinese wages allowed export prices to remain subdued. Now, it is becoming clear that much of this apparent economic dynamism was an illusion, more the product of profligate infrastructure projects and ghost city construction than productive investment.

The conjunction of these two US economic trends – soaring commodity prices and low inflation – should have put the lie to the idea that “price shocks” are the root cause of inflation. Even today, many economists still blame our current inflation on Covid-related “supply shocks,” not on fiscal and Federal Reserve profligacy.

As you can tell, I do not have what I would consider to be a compelling hypothesis to explain either the Euro’s dramatic rise or the spike in commodity prices, or, for that matter, how these two factors may have played into the BFC. I think that the important thing is that these are just two more stark examples of the era’s immense financial imbalances. Once again, the BFC is seen to be far more complex, and far more international, than is commonly appreciated.

Bad Management

By placing the onus for the BFC on Basel, I don’t mean to let financial managements entirely off the hook. Management was execrable in many cases and probably criminal in one or two. Still, it is important to bear in mind that for the most part firms were just doing what firms are supposed to do: maximize shareholder value within the legal boundaries imposed by policymakers. Unfortunately, those boundaries were warped.

After all, the crisis didn’t happen all at once. Managements didn’t suddenly decide one day to bet the bank on PMBS and CDS. Rather, it was an incremental process. Quarter by quarter, with no leverage constraint, they did a little bit more of what had worked previously to increase their earnings and hopefully their share prices. The incremental risk was pretty much invisible to them. As Shin puts it:

“. . . . greater lending by banks leads to further compression of spreads and other measures of risk, which induces banks to lend even more. So, Basel II made banks and the financial system much more procyclical and prone to booms and crashes.” Once financials had jumped on the leverage train, they could not get off. To paraphrase Chuck Prince, “They shoot horses, don’t they?”

This is pure Minsky.

Derivatives and “Gamma Risk”

The causal role of derivatives in the BFC was important but poorly understood by most people. Information regarding derivatives was then and remains sketchy. But the broad parameters of the problem are clear.

Derivatives include options, futures, interest rate swaps, credit default swaps, currency swaps, and other even more arcane instruments. The risks of each category of derivative ranged from minimal to “toxic” and depended critically on whether one was a “buyer” or a “seller”. Financials tended to be net sellers of derivatives, which is the riskier side.

The derivative exposure of many financial firms was colossal. UBS’ derivatives book exploded from SF26 billion in 2001 to SF450 billion in 2007 (at which point it exploded for real.)

Most of the problematical derivatives were “private”. This heightened firm and systemic risk because there was no market-determined public price. Thus, their accounting value was entirely dependent on assumptions made by management (too often, by the traders themselves) with the imprimatur (aka “rubber stamp”) of the auditors. As the market moved against the risk seller, no one on the outside, or even, sometimes, on the inside, really knew what the derivative’s value or the firm’s exposure was.

Let’s take the purely hypothetical case of a CDS issued by AIG that pays the holder $100 if Lehman Brothers defaults on a bond. In 2007, it might have cost the buyer 50 cents, reflecting an extremely low probability of default. The day before Lehman’s announcement, perhaps it was worth $10. The next day it would have been worth almost the full $100. In one year, the cash claim on AIG would have multiplied by a factor of 200. This is known as “gamma risk” or convexity.

Actually, things were a bit more complicated than that. CDS sellers like AIG were typically obligated to post collateral to the buyer as the position moved against them. This ostensibly guaranteed that the seller would have the cash to honor its CDS. The principal reason for AIG’s failure was that when Lehman failed, the market moved too far, too fast, and AIG was unable to scrounge sufficient collateral. In several books and numerous articles, economist Gary Gorton and his associates at Yale clearly document this collateral collapse plus many other aspects of the BFC.

In practice, AIG probably tried to mitigate its risk by hedging at least some of its exposure. But hedging effectively is a challenge even under the best of conditions, and in the panic just before and after Lehman’s bankruptcy, with all spreads exploding wider, it was impossible. Whatever AIG’s hedging strategy may have been, if any, it clearly did not work.

I believe that the “gamma factor” played a more important role in the BFC that is generally recognized. Not only did potential Financial creditors face the uncertainty of the risks visible on a counterparty’s balance sheet, but they also knew its derivative losses might be multiplying by the minute. Under these conditions, no fiduciary in his right mind would lend to AIG or any similar counterparty.

A few more points concerning derivative’s role in the BFC:

Some of the instruments often referred to as “derivatives” were not actually derivatives. The CDO’s that were famously “sliced and diced” in “The Big Short” were not derivatives.

In the lead up to the BFC, traders and financial managers did all they could to transmute assets into derivatives and jam them into the trading book where accounting standards were hazy, capital requirements were minimal, and the firms themselves were in control of valuation.

There were major differences between US GAAP and European accounting standards for derivatives. Most prominently, US companies were allowed to report “net” exposures to individual customers. This had the effect of making European banks appear much more leveraged than US companies.

Federal Reserve Monetary Policy

The Federal Reserve has drawn much criticism for keeping interest rates “too low for too long.” I am unconvinced that this had much to do with the sub-prime bubble, though it must have had some; if Alan Greenspan had jacked short term rates to, say, 5% in 2002 it probably would have prevented a bubble from forming. Of course, it also would have sent the economy into a tailspin.

One unintended consequence of low interest rates was that they enabled mortgage brokers to offer extremely low “teaser” rates that seemed affordable to borrowers — initially. Then, as the Fed raised rates in 2005 and 2006, payments increased and many of these borrowers defaulted.

Debauched Credit Standards

Credit standards slipped as the 2000’s progressed. This is normal for economic expansions, as noted by Hyun-Song Shin above and as expounded at lugubrious length by Hyman Minsky. Minsky once said, “Any period of financial stability is just a rubber band waiting to snap.”

But the massive losses suffered by financials in the panic were far more a function of liquidity risk than credit risk. As noted above, most of the securities that were written down 20-50% in the heat of the crisis ended up money good.

Rating agencies shared culpability for the crisis. Moody’s and their ilk are always dependable lagging indicators of credit downturns. Astonishingly, just as the conflagration was igniting in 2007, Moody’s actually raised Deutsche Bank’s rating from Aa3 to Aa1, one step below its highest Aaa rating. Not only were many pre-crisis ratings unjustifiably inflated, but rating agencies also inflamed problems with knee jerk downgrades in the heat of the panic of securities that mostly ended up money good.

Advent of the Euro

As noted above, the 1999 advent of the Euro opened the floodgates to Eurobank lending to other Euro member countries.

Deregulation

When discussing the role of deregulation in the BFC, many people cite the “Gramm Leach Bliley Act” for allowing “banks” to engage in all sorts of nefarious activities that were previously off limits. But really, there was very little that banks could do after Gramm Leach Bliley that they couldn’t do previously. Even an economist as liberal as Alan Blinder has acknowledged that “the case that tearing down the Glass-Steagall walls was a major cause of the crisis is an urban myth. “

Deregulation did contribute to the crisis, but in ways that remain obscure to most observers. We have mentioned the reduction in net capital rules for US broker-dealers. Most of the other changes, like the liberalized “recourse rule” mostly facilitated Financials’ ability to employ short term financing, especially repo. In his book “Unfinished Business”, Tamim Bayoumi ably details these arcane changes.

Of course, one could contend with some justification that Basel itself was, de facto, an act of deregulation. As we have seen, Basel I enabled Financials to take on excessive leverage, and Basel II significantly reduced regulatory oversight of European banks. It is also clear that the largest international banks were intimately involved in structuring the provisions of both Basels. But Basel’s original intent was never to deregulate, let alone make the world banking system riskier. It was intended, rather, to unify worldwide bank regulation.

Lax Audits and Examinations

From at least 2000 to 2006, regulators took a hands-off approach to the supervision of both Banks and Financials. Partly, this was because their attention was diverted to national security issues following the tragedy of 9/11.

But mostly, this permissiveness reflected the era’s free market zeitgeist. Basel I allowed European banks to value their own trading books. When Basel II extended this policy to loan books, European regulators effectively abandoned all bank supervision.

Bear in mind that European banks and US Shadow Banks (i.e. “Financials”) were the ones most responsible for the BFC. The former was regulated by the authorities of the nation in which they were headquartered, and the latter were only lightly regulated, if at all.

It should be stressed that then as now, large US commercial banks like Citi had armies of regulators permanently stationed in their organizations. Examiners at commercial banks like Citi and Wachovia knew all about the derivatives, SIV’s, ABCP, PMBS, that the banks were later castigated for. Thus, the failure to detect individual bank problems problems was nearly as much the fault of regulators as the banks themselves. The failure to identify systemicproblems was the fault of the regulators alone.

US Housing Policy

Federal housing policy and in particular Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (the GSE’s), greatly amplified systemic problems. It has been singled out by some experts as the primary cause of the crisis. Peter Wallison lays out the argument clearly in his FCIC dissent and his excellent book “Hidden in Plain Sight.” I find it difficult to isolate the impact of housing policy, but the impact was significant.

Starting in the mid-1990’s Congress steadily raised mandates for GSE lending to low-and-moderate income borrowers. For Fannie and Freddie such high-risk assets increased from 40% in 1995 to 58% in 2008. In 1999, only 7% of Fannie Mae’s loans to less advantaged borrowers had loan-to-value ratios of 95% or above. In 2008, that number was 41%. At the FHA, the percentage of purchase loans with loan-to-values over 97% more than doubled from 24% to 57% in just four years from 1998 to 2002.

The dumbing down of credit standards by the GSE’s forced private mortgage companies to stretch ever further out the risk spectrum to scrounge sub-prime volume. Of course, they didn’t care how sketchy these loans were as long as they could sell them on to a third party. And until 2007, they could sell just about anything in any quantity. I disagree that housing policy was the principal driving force behind the crisis, but it was certainly a major contributor.

In addition to the CDS that “wrapped” most PMBS, many had private insurance that “guaranteed” the principal and interest payments of the AAA tranches. Plus, many of the underlying loans had private mortgage insurance designed to pay the lender if the borrower defaulted. Both vehicles helped foster the illusion that PMBS were less risky than they actually were; as it turned out, the actuarial assumptions underlying this insurance were way off base, leaving the insurance companies hopelessly under reserved and over leveraged, like everyone else. When the panic hit, most of these insurers failed and could not honor most of their commitments.

Basel II

Basel II was promulgated in 2004 and was not adopted by any European bank until 2008. Still, it had a big impact on the buildup to the BFC. The bones of the plan were well known by the early 2000’s, and by 2004 at least, banks had begun to game the system.

Basel II allowed banks to value not only their own trading books, but also their own loan books. Thus, the essence of Basel II was the total abdication by European regulators of any role in bank supervision.

Perhaps that’s too harsh; regulators retained responsibility for approving bank valuation models. This enhanced the role of “the quants”, whose mathematical models supported traders.

The rise of the quants is a fascinating sidebar to the crisis. Basel I had enshrined a risk model for bank trading books known as “Value at Risk” (VAR). For bank loan portfolios, Basel II followed up with the “Vasicek Model.” This is not the place to discuss these models in detail, or the economic theories behind them. But let’s just say that as applied by Basel, these models were suspect. Oldrich Vacicek himself objected to how Basel applied his model. Here is Faisal Islam, “So the original author of the models that currently determine the safety of the world’s biggest banks says that those models are wrong.”

VAR had already been proven deficient in the collapse of Long-Term Capital and had been convincingly dismantled theoretically by such thinkers as Benoit Mandelbrot and Nassim Taleb. VAR is predicated on the assumption that risk is “normally distributed” – like a bell curve. Mandelbrot and Taleb argued – rightly – that major downturns in most markets happen far more often, and are far more severe, than can be explained by the normal distribution. This should have been common knowledge, but was never factored in by the quants, perhaps because it didn’t suit their purposes.

As years passed, managements gradually ceded power to the traders and quants. While there were numerous warnings about risk levels (see Rajan Raghuram in 2005), most managements felt they couldn’t afford to kill the golden goose. And anyway, it had all been blessed by Basel. This does not absolve management, but it does help explain how it all came about.

Sub-prime lending

I think I have already discussed sub-prime lending in sufficient detail.

The “Savings glut”

To account for the source of funds that fueled the BFC, many experts (notably Ben Bernanke) have theorized that the source was a global “Savings Glut”. This glut, they said, arose from strong economic growth, high savings rates, and large trade surpluses in Germany, Japan, and, especially, China.

But there are problems with the savings glut hypothesis. First, the foreign trade surpluses were not nearly big enough to account for the huge amount of foreign credit that flooded into the US. Also, these nations bought only US treasuries and agencies, not PMBS.

Hyun-Song Shin’s “The Global Banking Glut” appeared in 2012 and should have disabused everyone of their Savings Glut theory. The article pointed out what should have been obvious to everyone; the funds that fueled the crisis came from the growing leverage of Basel regulated financial institutions. Why Shin’s insight did not immediately gain traction and become the consensus view is a complete mystery to me.

Commercial Bank Construction Loan Losses

As noted above, few US commercial banks had any direct exposure to sub-prime loans, securities, or derivatives. But many Banks did have significant exposure to construction loans that financed the new housing product. Low interest rates, together with the sub-prime mania drove a surge in house prices and a tsunami of demand and home building. Small and mid-sized regional banks had the most exposure. Many suffered losses, and some failed when the housing market collapsed. But overall, commercial banks emerged from the crisis badly bent but far from broke. (See my blogpost “Tale of Two SIFIs”.)

Fraud, Greed, and Moral Hazard

We touched earlier on the role of fraud. Just one more point.

Low level (but highly compensated) sub-prime mortgage agents committed by far the bulk of any fraud that was perpetrated in the BFC. These individuals were overwhelmingly employed by non-bank mortgage companies like New Century Financial and Countrywide. Much of what they did was more deception than outright fraud: documentation contained all the required information. That doesn’t make their behavior acceptable, but it does make it difficult to prosecute.

“Mark-to-Market” Accounting (Including an SIVB post-mortem)

The same free market mindset that produced Basel also gave us “Mark-to-Market” (MTM) or “Fair Value” accounting. The theory behind MTM rests on the “Capital Asset Pricing Model” (CAPM) which holds that a security’s market price always accurately measures its true underlying economic value. CAPM assumes that the market price always encapsulates all knowledge of perfectly informed investors and always captures the true intrinsic value of the security’s underlying cash flows. Essentially, it assumes that investors understand everything with flawless accuracy. My years on Wall Street, and my common sense, have made me skeptical of this hypothesis.

For a number of reasons, I have always been an intractable opponent of MTM. Above all, I believe that it violates the most fundamental accounting precept: that firms should be evaluated as “going concerns”, not on a liquidation basis.

Mark-to-market accounting has been imposed very selectively. It was mainly imposed on banks and insurance companies. Perversely, it was only applied to one side of their balance sheet: the asset side. About the best thing one can say about MTM is that in stable financial markets, it is not hideously misleading.

But in the roiling post- Lehman BFC, the impact of mark-to market accounting was catastrophic. As panic ensued, liquidity evaporated and “price discovery” became impossible. Gaping spreads blew out between bid and ask prices. Desperate firms and those with small PMBS exposures hit those bids, driving prices down further. As noted earlier, many AAA PMBS prices were driven down 40-50% even though their “true” economic value, as we now know, was par.

In this environment, any attempt to ascertain the “true” value of an asset, let alone determine the solvency of the asset holder was a fool’s game. MTM made the panic far worse than it otherwise would have been.

For a lucid and thorough critique of mark-to-market accounting as applied during the BFC, see chapter 12 of Peter Wallison’s “Hidden in Plain Sight”. Wallison focuses on the inherent pro-cyclicality of mark to market accounting, which inevitably amplifies bank problems and the volatility of economic cycles. Wallison also examines the impact of the ABX index and the role of the rating agencies. Plus, he examines in detail the issues involved in valuing specific PMBS securities.

Today, with the 10-year yield rising inexorably toward 5%, mark to market accounting is once again working its insidious harm. As interest rates rise and bond values drop, banks are forced to incur mark-to-market losses on their securities portfolios. For most banks, these markdowns have reduced their equity which, in turn, constrains their capacity to lend money.

The problem is that these MTM-driven write downs are often a highly misleading representation of a bank’s intrinsic value. In fact, rising interest rates have benefitted many banks. Yields on assets have risen faster than the rates paid on deposits, so bank “net interest margins” have mostly widened. Thus, the value of the bank has increased even as “mark-to market” accounting has forced banks to write down their equity.

The graph below shows that aggregate banking industry profits are now at record highs.

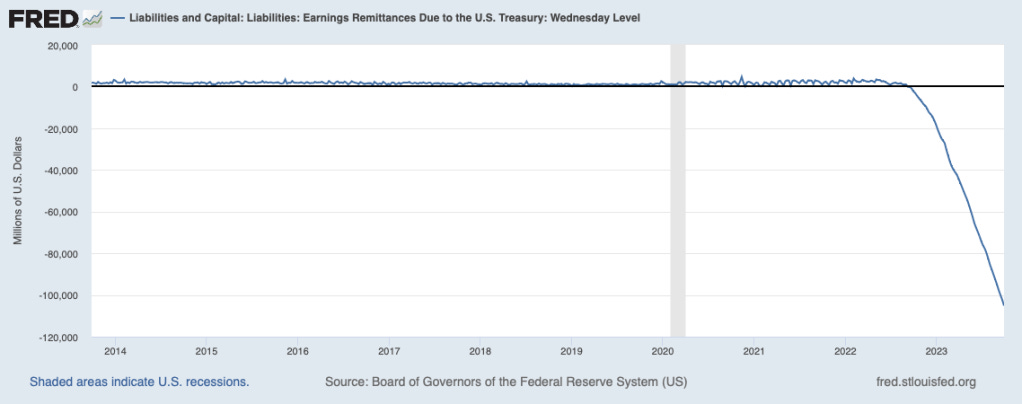

The next graph shows that despite record profits, the banking industry recently has taken equity write downs far in excess of the write-downs they took in the BFC. You don’t need a CPA to appreciate that these write downs woefully distort economic reality. But the repercussions are not merely theoretical; access to bank credit has been attenuated throughout the economy.

Consider this extreme and highly simplified example: a hypothetical bank with $1 billion in demand deposits and $100 in equity. Assume that its demand deposits pay no interest, as DDA seldom does. Then assume that back in 2021, trusting Jerome Powell’s promises of transitory inflation, it chose to use its funds to buy $1.1 billion in 2% 30-year Treasury bonds (something no actual bank would ever do.) Thus, the bank has “locked in” a spread of 2% or $22 million annually.

Today, the 30-year yield has risen to 4.75% and the value of the bank’s 2% bond has plummeted by nearly 50%. Based on “mark-to-market” accounting, the bank is now insolvent and must be shut down. But the true “going concern” value of the bank has not changed. As long as its deposits stay put, there will be no impact whatsoever on the bank’s earnings prospects, or on the bank’s value. To look at it another way, the decline in the market value of the bank’s bonds is entirely offset by an increase in the market value of its deposits. In a real world undistorted by accounting whims, this bank can remain in business and continue to support its community.

But wait, you say, in real life wouldn’t the depositor move those zero percent deposits into deposits with a higher yield or into a money market fund? Answer: it depends. Most bank customers, whether individual or corporate, must retain some amount of DDA to effect transactions. The question is: how much?

Bank asset / liability management is more an art than a science. Recently, the biggest challenge has been estimating the “staying power” of the low-cost deposit base that burgeoned in the zero rate environment following the BFC. In this low rate world – and especially post COVID – banks accumulated huge endowments of low-cost deposits. The government shoved trillions in cash into the coffers of consumers and corporate treasurers, who parked it in low-cost deposits. Meanwhile, the Fed bought securities and plowed reserves into banks, artificially suppressing longer term rates. There was little incentive for any depositor to look for higher interest rate alternatives than DDA: there were none. So excess savings lingered in demand deposits paying no interest.

When inflation gained traction in 2022, the Fed panicked (yet again) and started jacking up short term interest rates and shrinking its balance sheet. This removed bank reserves, shrank system deposits, and caused interest rates to rise sharply all along the yield curve. Suddenly, depositors started doing the rational thing, shifting funds out of 0% deposits and into higher yielding accounts.

Thanks to QT, all banks have suffered erosion of their core deposit bases, but some have managed this transition far better than others.

The worst, of course, was Silicon Valley (SIVB). Of all US banks, SIVB in 2021 boasted one of the largest endowments of DDA as a proportion of its assets. In the event, SIVB seriously overestimated the “staying power” of these deposits. As rates rose, corporate treasurers shifted funds to higher-yielding assets both within and outside the bank. More seriously, as the tech cycle turned, funds ceased flowing into tech investments and tech startups started running down their bank balances. Worst of all, SIVB’s security portfolio had an average duration of more than 6 years, irresponsibly long for any bank. There has been some speculation that the coup de grace came when just one or two prominent investors instructed their companies to remove funds from the bank. This instigated a run on SIVB and brought about its ultimate failure.

Because the Fed chose not to support SIVB, First Republic got caught in the whirlpool and was sucked down. Signature bank failed largely due to its association with crypto. (A key, but widely ignored trigger for all these failures was the collapse of Silvergate Bank just days before SIVB suffered its run. Silvergate’s failure is hardly mentioned in the Fed’s otherwise commendably candid report on SIVB’s failure. A dedicated crypto bank, Silvergate’s demise spread panic among depositors in any bank with crypto exposure. This group prominently included tech companies, executives, and venture funds. It is my suspicion that when the final chapter on SIVB’s failure is written, the most culpable party may well be regulators for permitting Silvergate to become so concentrated in crypto.) But despite prophecies of imminent doom from the likes of CNBC, no other large bank has had problems that were even remotely as serious as these three.

Many in the media like to claim that bank deposits are “fleeing banks into the safety and higher returns of money market mutual funds.” But this is a gross overstatement. When a depositor elects to move funds to a money market mutual fund (MMMF), she wires funds to the MMMF which then uses those funds to buy securities. If the MMMF then uses those funds to buy a corporate security or anything on the open market, those funds will then become deposits in the seller’s bank accounts. There is no change in systemic deposits. But, as James Mackintosh at the WSJ points out, if these funds are used to buy Treasuries in an auction, the deposits will leave the system.

There are only three ways for the financial system itself to gain or lose reserves or deposits: First, money is created when a bank makes a new loan and is removed when a loan is repaid. Second, the Fed can increase or decrease the size of its balance sheet. Lastly, government spending can increase the money supply and taxation will reduce it, conditional on the Fed’s concurrent policies.

Today, deposits are indeed leaving the banking system, but not due to depositor fear or high interest rates. Rather, deposits are shrinking because the Fed has decided to reduce its balance sheet, thereby strangling the industry and, ultimately, the economy of liquidity. This strategy was last pursued in 1932 and produced the Great Depression. Hopefully, results will be better this time around But Jerome Powell’s track record does not inspire confidence.

One final point. With breathtaking hypocrisy and hubris, the Federal Reserve exempts itself from the very same “mark-to-market” accounting standards it so unwisely imposes on banks. Having conjured inflation and raised short term interest rates, the Federal Reserve is now insolvent to the tune of a hundred billion dollars. Any bank with a balance sheet that looked remotely like the Fed’s would immediately be shut down and its management indicted.

For what it’s worth, having labored in successful hedge funds for decades, I learned one thing for sure; if the market price ever reflects an asset’s true economic value, it is sheer coincidence.

WE HAVE MET THE ENEMY, AND HE IS US

Finally, with some trepidation, I would like to assert that the greed of American homeowners played a crucial role in creating the BFC. I’m hoping that enough time has passed to have removed the taboo from this topic. To contend that all of us were complicit in causing the BFC is not to “blame the victim.” It is to state the obvious.

There was clearly something very strange about the pre-crisis American zeitgeist. The “American Dream” during the early 2000’s seems to have morphed into a culture of entitlement, or at least inflated expectations.

A fascinating 2003 Gallup poll underscores this sentiment. I remember being shocked when I read the poll at the time. It was quite simple; it asked a randomly selected group of Americans the following question:

Do you expect to be rich at some point in your lives? (“rich” was defined as an income of $200,000 or more or assets of more than $1 million.)

Fully 30% of all Americans and 50% of those under age 30 answered “yes.” This was not the American Dream. This was freakin’ mass psychosis. In fact, only about 3% of the country topped those hurdles at the time. People were not asked how they intended to achieve this wealth, and I have no indication of how a poll like this might have looked in the past. But I’m pretty sure that a similar poll conducted today would produce very different results.

I am convinced that the myths prevalent pre-crisis help explain our nation’s subsequent descent into post-BFC social and political factionalism. (See my post “The Tribe has Spoken.” ) Simply put, Americans who were young adults in the early 2000’s are deeply resentful about not being rich. And being human, they are certain that their disappointments cannot possibly be their own fault. Everyone believes that his birthright has been unfairly snatched by liberal elites, or the “deep state”, or systemic racists, or bankers, or immigrants, or the 1%. For comfort, we all withdraw into our preferred tribes to rail at “the other” and nurture our illusions of victimization. I pray that somehow we can restore our former unity, such as it was, but I’m not holding my breath.

A POPPER CONCLUSION

As a big fan of Karl Popper, I feel duty-bound to conclude by asking, “What new information might I uncover that would weaken, or even falsify my current views.”

I can imagine only one thing that might change my views concerning Basel’s central role in the BFC. That is, if someone could produce a more convincing alternative explanation for the excessive systemic pre-crisis leverage. In the fifteen years since the crisis, I have not yet seen any compelling, or even enticing, evidence of such an alternative.

Similarly, I am unlikely to change my conviction that US banking regulation has become excessively repressive and counterproductive. Of course, most regulators and politicians consider the post-crisis regulatory world to be a rousing success: no big bank has failed (until SIVB.) But this stability has come at an immense cost both to the banking industry and the overall economy.

It has always been puzzling to me that the runup to the BFC does not seem to be reflected in aggregate economic numbers, especially monetary assets. To inflate a bubble of that size, one would expect to see excessive money supply growth or credit growth somewhere in the world.

True, US bank credit grew at a compound rate of just over 10% per year from 2004 to 2008, This is rapid, but not out of line with prior US economic expansions. (If one adjusts for inflation, it looks as if aggregate loan growth was 2-4% greater than in past expansions. This needs further investigation.) Money growth in these years was in the 6% range. It was higher in Europe and higher still in the UK, but again, nothing that would have led one to think that a catastrophic bubble was inflating.

I suspect that the apparent normality of aggregate trends might conceal the real problem: much of the sub-prime loan volume in the US came from “cash out refinancing” of conventional mortgages. This meant that the sub-prime, refinanced mortgage was only moderately larger than the loan it replaced. If this is so, then the sup-prime mania would have produced little NET increase in aggregate US credit. But the entire mortgage market would have become much riskier.

This hypothesis is supported by balance sheet trends for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. In 2004, total GSE assets (both on-balance sheet and guaranteed) measured nearly 50% those of the entire banking system. After growing by nearly a trillion dollars between 2000 and 2004, GSE balance sheets abruptly stopped growing and began to shrink. This was largely due to a 2004 Congressional investigation into the GSE’s accounting improprieties. The GSE’s pulled back sharply on purchases of conventional mortgages. At the same time, GSE subprime commitments continued to increase. This may have enabled subprime mortgage companies to capitalize on the GSE’s absence by issuing subprime product.

The Basel Financial Crisis: A Brief Personal Memoir

At the risk of self-indulgence, I would like to share a bit of my own experience during the BFC that might be germane. From 2000 to 2015 I worked as a portfolio manager for a “market neutral” hedge fund that was part quant and part fundamental. By “market neutral” I mean that for every dollar of stock that we owned, we religiously were short an equal amount. Our track record was, I think, excellent. I was responsible for most of the financial services and real estate related portfolios.

Those of us who were banking “experts” could see the crisis approaching in early 2007 because bank construction loans, after a dramatic runup in the years 2002-2006, started going sour in late 2006. The residential real estate markets had clearly peaked, especially in what had been the hottest markets like Las Vegas, Phoenix, and California’s “Inland Empire.” Real estate construction exposures at many smaller banks were clearly excessive. Even more worrisome, subprime originators started blowing up all over the place.

We also knew that the biggest international financial institutions were absurdly over-leveraged. We used to joke that if Barclays marked its derivatives portfolio on the bid side instead of the offer, they’d be out of business. But few, if any, of us understood how much of this leverage resulted from US operations.

One day in early 2007 I went to a meeting with Anglo-Irish Bank, an Irish bank with US operations. As I looked at its financial statements before the meeting, I was appalled. Its construction loan concentration was off the charts, and much of it was US based. Its funding was almost entirely short term; it had no US deposit base.

I respectfully suggested to management that they should pull back their lending immediately because they would fail if a recession hit. They did not take (or even appreciate) my advice, and they did ultimately fail. This was when it first dawned on me that European banks might be deeply involved in United States real estate lending.

I had a similar premonition of disaster when I visited the management of Sterling Financial, a Seattle-based thrift. Their construction loan portfolio had been growing like a weed and I wanted to get details. The CEO told me that most of the loans were for projects in the southwest, mainly Phoenix and Las Vegas. When I asked whether he thought that was prudent, he responded by assuring me not to worry, the “conduits” would always take him out of any completed project. When I asked him what, exactly, a conduit was, he clearly didn’t know.

I had seen this movie before. Since around 1980, when computer power made mortgage-backed securities possible, there had been firms whose business models centered on asset generation for the sole purpose of selling those assets on to a third party. The third party – the “conduit” – then packaged these loans into a security and sold it.

For the asset securiitizer and even more so for the originator, there are two fatal flaws to this business model. First, to continue to generate assets and feed the beast, the originator must steadily move further and further out the risk curve. Second, and more importantly, both sides typically rely on short-term borrowing to finance their inventory until they have enough to sell.

If market conditions change, as they inevitably do, investors will stop buying the securities and markets will “freeze up” (a Minskyian “financial revulsion”). Then, the securitizer will have a serious problem but it will be far worse for the originator. The originator will not only hold inventory that must be financed, but it will also be committed to closing on much more. Concerned about credit risk, creditors will be unwilling to finance these new assets and the originator will fail.

To me, then, the craziest thing about the BFC was that there had just been a subprime bubble and crash less than a decade earlier in the 1990’s. Who among us older folks can possibly forget Dan Marino for FIRSTPLUS or Phil Rizzuto for the Money Store? Employing the same business model that would later blow up in the BFC, subprime lenders originated loans for sale to investors and ultimately choked on them when liquidity evaporated. When the subprime business once again hit the skids in the late 2000’s, a mere ten years after its previous implosion, for many of us it was, well, “deja vu all over again.” (To my knowledge, Yogi never endorsed a subprime lender, only Yoo Hoo.)